18th century America was impacted and influenced by the so-called Glorious Revolution in the Motherland. And no-one had a bigger impact on American attitudes towards freedom of speech than Cato’s Letters written by the Radical Whigs John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon. Cato´s Letters created a powerful free speech meme, that went viral in the colonies: “Freedom of Speech is the great Bulwark of Liberty”. The reach of Cato’s principles grew exponentially as colonists liked, shared and commented on them in newspapers, pamphlets and taverns. Americans were persuaded that “Without freedom of thought, there can be no such thing as wisdom; and no such thing as publick liberty, without freedom of speech: Which is the right of every man”. As a consequence, grand juries and juries refused to indict and convict colonists for seditious libel when criticizing governments and officials.

Despite the practical defeat of libels laws in colonial courts, legislative assemblies continued to threaten free speech. Under legislative privilege provocative writers could be jailed and fined by their own representatives. And even American heroes were sometimes willing to sacrifice principle.

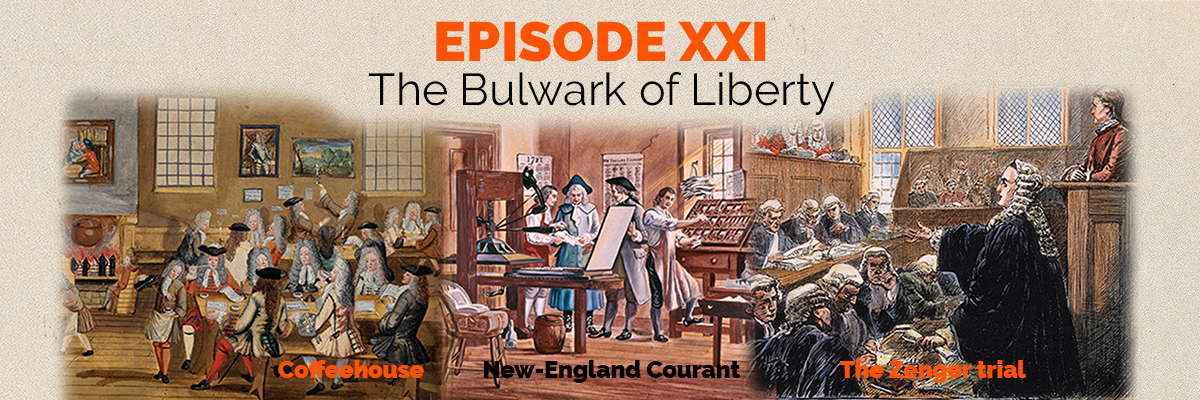

In this episode we’ll explore

- How coffee-houses expanded the public sphere by cultivating the sharing of news and ideas, including revolutionary ones.

- How the common law crime of seditious libel impacted writers

- How English writers including Matthew Tindal, John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon paved the way for American ideas on free speech

- How the editor of the New England Courant in Boston combined anti-vaxxer propaganda with free speech advocacy

- How the 16-year old Benjamin Franklin used Cato’s Letters to argue for freedom of speech when his brother James was in jail

- How the New York Weekly Journal became America’s first opposition newspaper and justified its savage hit pieces on New York governor William Cosby with Cato’s free speech principles

- How a jury acquitted the printer of the New York Weekly Journal Peter Zenger, even though he was guilty according to the law

- How legislative privilege was used to punish colonialists for offending their own representatives

- How Benjamin Franklin defended legislative privilege and the jailing of a Pennsylvania man for his writings

You can subscribe and listen to Clear and Present Danger on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, YouTube, TuneIn, and Stitcher, or download episodes directly from SoundCloud.

Stay up to date with Clear and Present Danger on the show’s Facebook and Twitter pages.

Email us feedback at freespeechhistory@gmail.com.

Litterature:

- Allison, R. (2015). The American Revolution. Oxford University Press. Kindle edition.

- Armoy, H., & Hall, D.D. (2000). The Colonical Book in the Atlantic World: A History of the Book in America vol. 1. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Bailyn, B. (1967). The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bogen, D.S. (1983). The Origins of Freedom of Speech and Press. Maryland Law Review 42(3), pp. 429–465. Retrieved from here.

- Colombia Law School (2018, December 3). The Free Speech Century: How the First Amendment Came to Life. Retrieved from here.

- Curtis, M. (2000). Free Speech: ”The People’s Darling Privilege”. Durham/London, UK: Duke University Press.

- Duniway, C.A. (1906). The development of freedom of the press in Massachusetts. New York, NY: Longmans, Green, and co.

- Eldridge, L. (1994). A Distant Heritage: The Growth of Free Speech in Early America. Kindle edition. NYU Press.

- Hargreaves, R. (2002). The First Freedom: A history of free speech. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing.

- Kramnick, I. (1992). Republicanism Revisited: The Case of James Burgh. Proceedings of the American Antiquiarian Society 102, pp. 81-98. Retrived from here:

- Levy, L.W. (1995). Blasphemy: Verbal Offense Against the Sacred, From Moses to Salman Rushdie. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press

- Levy, L.W. (1987). The Emergence of a Free Press. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Linder, D.O. (n.d.). Key Figures in the Trial of John Peter Zenger. Famous Trials. Retrieved from here.

- Martin, R.W.T. (2001). The Free and Open Press: The Founding of American Democratic Press Liberty. New York, NY: NYU Press. Kindle Edition.

- Mayer, D.N. (1992). The English Radical Whig Origins of American Constitutionalism. Washington University Law Review 70(1) pp. 131–208.

- Mitchell, A., Matsa, K.E., Gottfried, J., Stocking, G., & Grieco, E. (2017, October 2). October 2, 2017. Covering President Trump in a Polarized Media Environment. Pew Research Center: Journalism & Media. Retrieved from here.

- Encyclopedia of Philosophy (n.d.). Tindsal, Matthew (1657?–1733). Retrieved from here.

- Noyes, R. (2018, October 9). Study: Economic Boom Largely Ignored as TV’s Trump Coverage Hits 92% Negative. Media Research Center NewsBusters. Retrieved from here.

- Solomon, S.D. (2016). Revolutionary Dissent: How the Founding Generation Created the Freedom of Speech. Martin’s Press. Kindle edition.

- Standage, T. (2013). Writing on the Wall: Social Media – The First 2,000 Years. New York, NY: Bloomsbury

- Taylor, A. (2002). American Colonies: The Settling of North America (The Penguin History of the United States vol. 1), revised edition. Penguin Books. Kindle edition.

Primary sources

- BY THE GOVERNOUR AND COUNCIL (1690, September 29). Retrieved from here.

- Franklin, B. (1737, November 17). On Freedom of Speech and the Press. The Pennsylvania Gazette. Retrieved from here.

- Franklin, B. (1758, April 27). Documents on the Hearing of William Smith’s Petition. Retrieved from here.

- New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964). Retrieved from here.

- PUBLICK OCCURENCES, both FORREIGN and DOMESTICK (1690, September 25). Retrieved from here.

- Tindal, M. (1704). Reasons against restraining the press. Retrieved from here.

- Tindal, M. (1709). A Discourse for the Liberty of the Press. Four Discourses. Retrieved from here.

- Trenchard, J. (1720, February 4). Cato’s Letter no. 15: Of Freedom of Speech: That the same is inseparable from publick Liberty. Retrieved from here.

- Trenchard, J. (1721, June 10). Cato’s Letter no. 32: Reflections Upon Libelling. Rerieved from here.

- Trenchard, J. (1722, October 27). Cato’s Letter no. 100: Discourse upon Libels. Retrieved from here.

Trenchard, J. (1722, November 3). Cato’s Letter no. 101: Second Discourse upon Libels. Retrieved from here.