FREE SPEECH HISTORY TIMELINE

Dive into a timeline covering the subjects of Clear and Present Danger. The timeline will expand as we travel through the history of free speech.

Free speech history

Episode I: Who wishes to speak?

Athens was the birth place of democracy, isegoria and parrhesia – the Greek words for equal and uninhibited speech. What did free speech entail for a comedian, a philosopher, an orator and the ordinary citizen of ancient Athens? Was Socrates a free speech martyr or a seditious enemy of democracy? And how far was Demosthenes willing go to become one of the greatest orators of ancient Greece? Find out in Episode I.

c. 508 BCE: The Athenian Democracy and Isegoria

The goddess of democracy crowning the people of Athens, c. 337 BC (Photo: Craig Mauzy)

The Athenians develop the world’s first democracy in the 6th century BCE. The right to isegoria or ‘equality of speech’ – including the right to address the assembly – is a cornerstone of Athenian democracy.

This is how the orator Aeschines describes the Athenian assembly:

“the herald … does not exclude from the platform the man whose ancestors have not held a general’s office, nor even the man who earns his daily bread by working at a trade; nay, these men he most heartily welcomes, and for this reason he repeats again and again the invitation, ‘Who wishes to address the Assembly?’”

(Aeschin. 1.27)

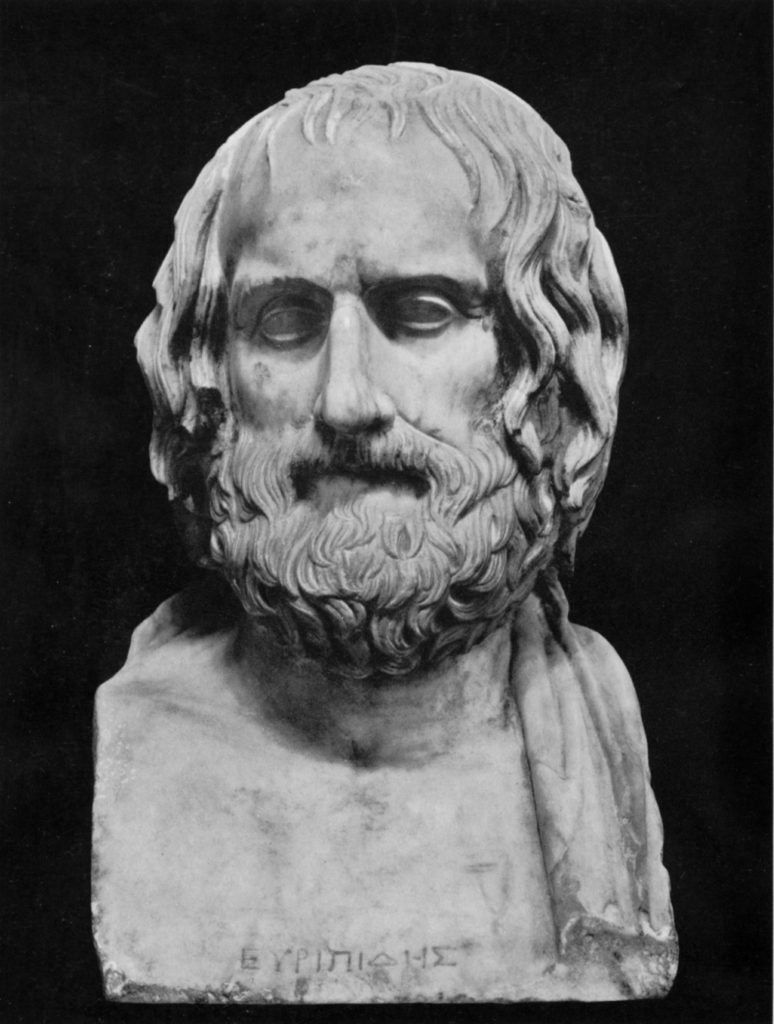

c. 480 – c. 406 BCE: Euripides and Parrhesia

Parrhesia or ‘uninhibited speech’ is another ancient Greek concept of free speech which means to speak freely, boldly or frankly. The term is first used by the playwright Euripides who depicts Athens as a place where all free males can speak freely when debating public issues.

In his play The Phoenician Women, Euripides declares that:

‘This is slavery: not to speak one’s thought’

– Euripides, The Phoenician Women

399 BCE: The Trial of Socrates

Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Socrates, 1787 (Public Domain)

In 399 BCE, the philosopher Socrates is found guilty of “refusing to recognize the gods recognized by the state” and “corrupting the youth”. He is sentenced to death by drinking poisonous hemlock. (Diog. Laert. 2.40)

Socrates’s pupil Plato later reconstructs his defense speech:

I know that my plainness of speech makes them hate me, and what is their hatred but a proof that I am speaking the truth?

– Socrates, according to Plato’s Apologia

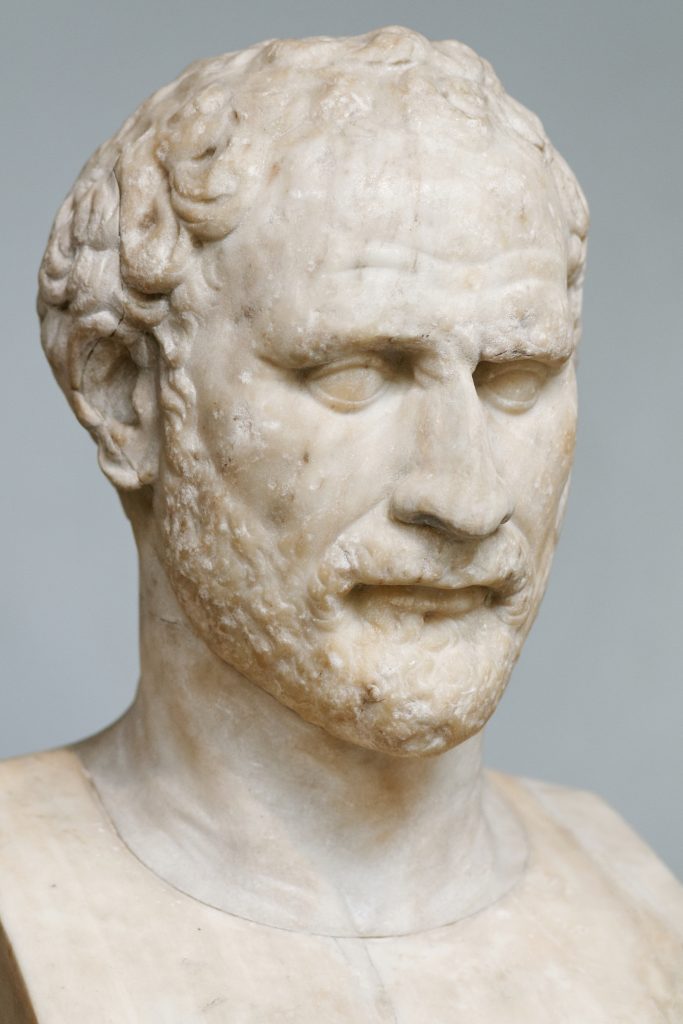

384-322 BCE: Demosthenes

Roman copy from Greek original, British Museum (Public Domain)

The orator Demosthenes is an unconditional proponent of parrhesia or ‘uninhibited speech’. In his discourse ‘On the Embassy’, he declares that:

“It is necessary to speak with parrhesia, without holding back at anything without concealing anything.”

C. 268-232 BC: Ashoka and the first declaration of religious tolerance

Ashoka’s iconic pillar of Sarnath, c. 250 BC (Public Domain)

In the 3rd century BC, the Mauryan king Ashoka inscribes a number of edicts in stone in present day India. The inscriptions include one of history’s first ‘declarations of religious tolerance’:

“Growth in essentials can be done in different ways, but all of them have as their root restraint in speech, that is, not praising one’s own religion, or condemning the religion of others without good cause. And if there is cause for criticism, it should be done in a mild way.”

– The Edicts of King Ashoka

c. 213 BC: The Qin Emperor and history’s first book burning

Unknown illustrator, c. 1850 (Public Domain)

Around 213 BC, China’s first emperor Qin Shi Huang orders the burning of books on history and philosophy. This is the first book burning in recorded history.

“I have collected all the writings of the Empire and burnt those which were of no use”

– Emperor Qin Shi Huang (259-210 BC)

Episode II: Liberty or license?

Rome was the most powerful empire in the ancient world. But were the Romans free to speak truth to power? Who came out on top when the words of Cicero clashed with the ambition of Caesar and the armies of Octavian? And why did historians and astrologers become endangered species in the Roman empire? Find out in episode II.

c. 150 BCE: The invention of paper

According to acheological evidence, paper is invented in China in the 2nd century BCE. The first primitive paper is made from hemp.

In 105 CE, Cai Lun, the director of the Imperial Workshops at Luoyang, officially report the invention of paper to the Han Emperor.

Papermaking spreads to the Arab world from the 8th centuries. It is imported in Europe as a commodity from the 12th century.

509 BCE: Birth of the Roman Republic

The Romans swearing an oath over Lucretia’s body. Detail from S. Botticelli’s The Story of Lucretia, c. 1500. (Public Domain)

According to Roman legends, the Republic is born in 509 BCE when the Romans expel their last king and swear never to be governed by a tyrant again.

Liberty or libertas and equality before the law are cherished cornerstones in the Roman republic. According to the Roman historian Livy:

“the Romans… valued liberty first… no man stood above the law. They valued their liberty so much precisely because their last king had been so great a tyrant…”

– Livy, History of Rome 2.1

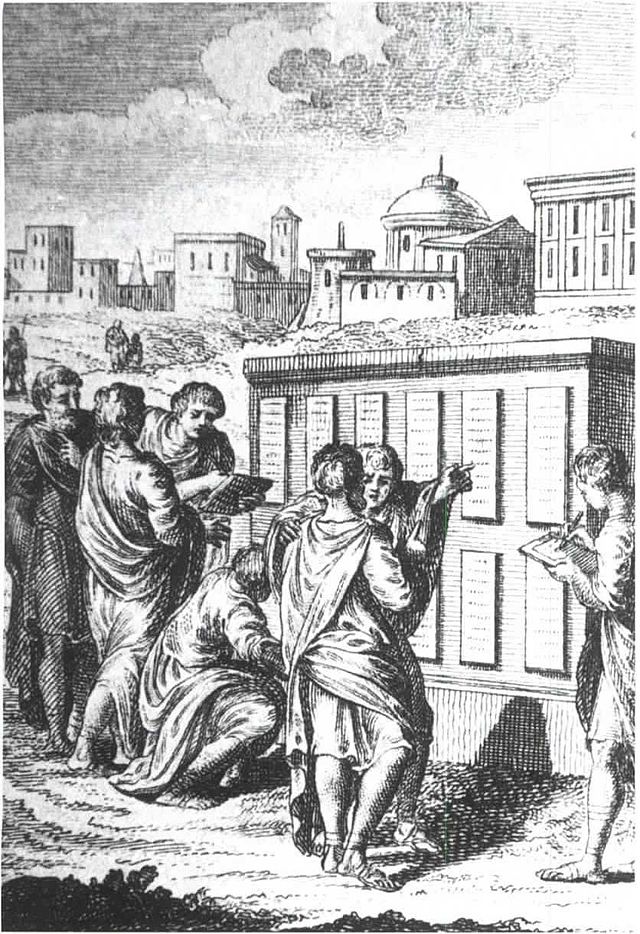

C. 450 BCE: The Twelve Tables

The Romans inscribe their first legislation on twelve bronze tables around 450 BCE. The law punishes speech crimes like slanders and libel with death. The tables are lost but can be reconstructed from the writings of later Romans:

“It was laid down that, if anyone was found to be uttering in public a slander, he should be clubbed to death.”

– Cornutus (ad Pers., S., I, 137)

“Our Twelve Tables, though they ordained a capital penalty for very few wrongs, among these capital crimes did see fit to include the following offence: If any person had sung or composed against another person a song such as was causing slander or insult to another . . .”

– Cicero (de Rep., IV, 12)

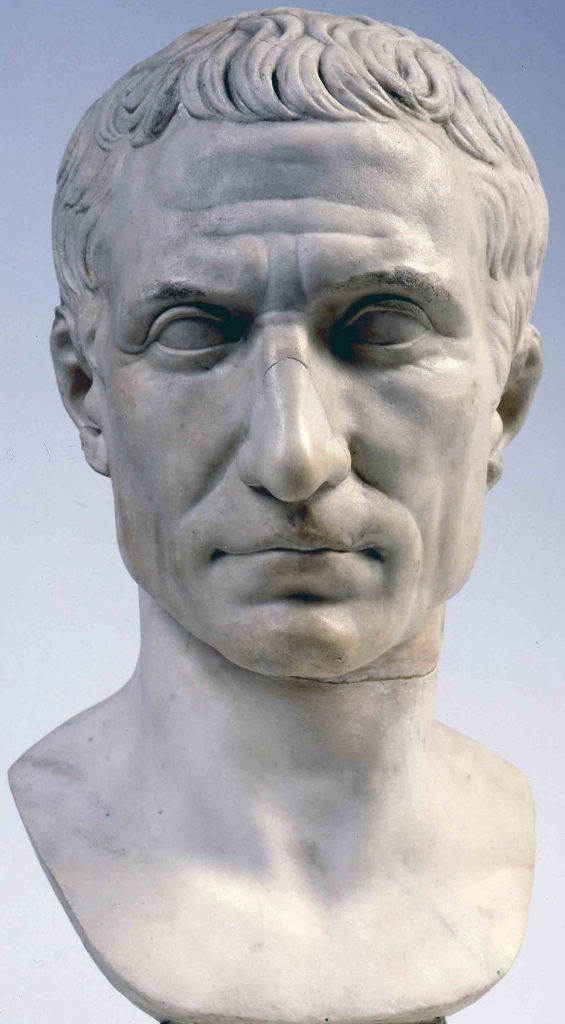

C. 100-44 BCE: Julius Caesar

The general and consul Julius Caesar is a controversial character in the history of free speech. When he becomes consul in 59 BCE, he opens the Senatorial protocols for the public. The published acta diurna can be regarded as the first newspaper in history. Instead of silencing his political enemies with force, he generally prefers to fight back with words. Caesar’s polemical response to Cato the Younger, the Anticato, is a brilliant example.

On the other hand, Caesar’s grab for power is one of the main reasons for the fall of the Republic and the loss of liberty. When he names himself ‘dictator indefinitely’ in 44 BCE, Republican senators like Cicero and Cato the Younger view him as a serious threat to Roman liberty.

“War has no use for free speech”

– Caesar, according to Plutarch’s The Life of Julius Caesar 35.7

106-43 BCE: Cicero

François Perrier, The Death of Cicero, 1635

During the last days of the Republic, Cicero uses his rhetorical gifts to defend Roman liberty from Caesar and Mark Anthony.

Cicero is assassinated by his political enemies in December 43. According to the historian Cassius Dio, his critical tongue is pierced with a hair pin while his body parts are displayed on the speakers’ platform in the Forum Romanum.

… I could not, on the one hand, endure to live under a monarchy or a tyranny, since under such a government I cannot live rightly as a free citizen nor speak my mind safely.

– Cicero according to Cassius Dio’s Roman History 45.18

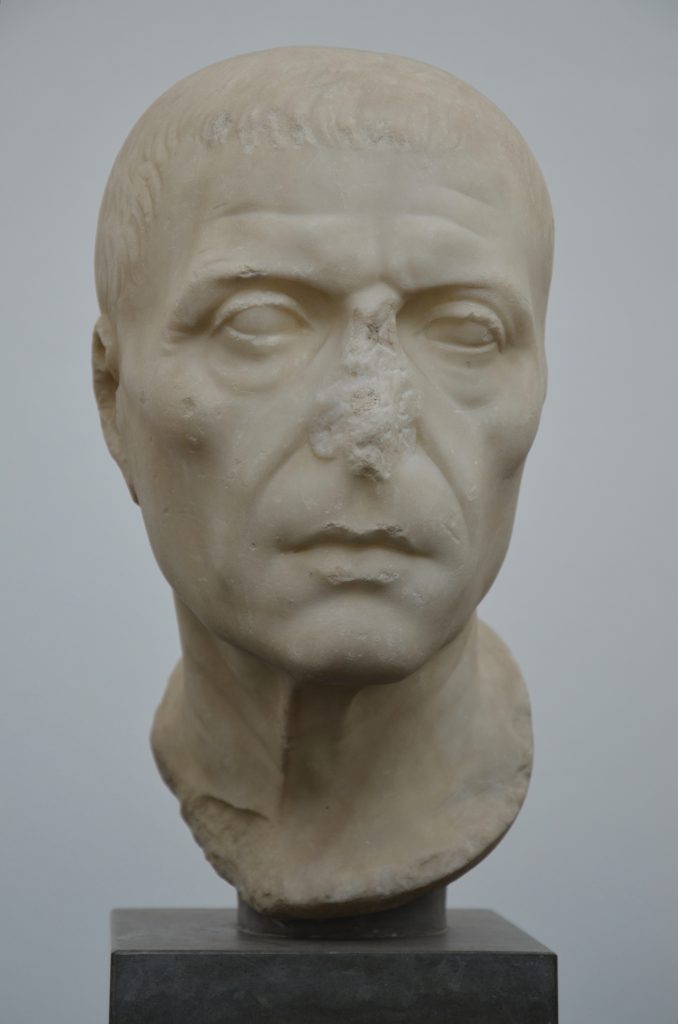

95-46 BC: Cato the Younger

Cato the Younger (Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek)

Cato the Younger defends the republic to the bitter end. According to Cassius Dio, he pulls out his own intestines when Caesar’s assumption of power.

“I, who have been brought up in freedom, with the right of free speech, cannot in my old age change and learn slavery instead.”

– Cato the Younger according to Cassius Dio, Roman History 43.10

27 BC – 14 AD: Augustus

(Public Domain)

Rome’s first emperor, Augustus, introduces punishments for “literary treason” and orders illegal texts burned.

It does not harmonize with his instruction to his adoptive son and successor, Tiberius, to distinguish words from actions:

“My dear Tiberius, do not be carried away by the ardour of youth in this matter, or take it too much to heart that anyone speak evil of me; we must be content if we can stop anyone from doing evil to us.

– Augustus according to Suetonius, Lives of the Caesars 2:51.

14-37 AD: Tiberius

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek (public domain)

Augustus’ successor Tiberius convicts speech crime offenders to death and burns the entire works of seditious writers. In 23 CE, the poet Aelius Saturninus is hurled to death from the Capitol Hill for “reciting improper verses about the emperor”. Two years later, the historian Cremutius Cordus is convicted of treason for calling Caesar’s assassins, Brutus and Cassius, “the last of the Romans”.

According to the historian Suetonius:

“Every crime was treated as capital, even the utterance of a few simple words. A poet was charged with having slandered Agamemnon in a tragedy, and a writer of history of having called Brutus and Cassius the last of the Romans. The writers were at once put to death and their works destroyed”

– Suetonius: The Life of Tiberius 61.2

25 AD: The trial of Cremutius Cordus

In 25 AD, the republican historian Cremutius Cordus is convicted of treason for calling Caesar’s assassins, Brutus and Cassius, the ‘last Romans’. Facing a death sentence, he starves himself to death. All his books are burned and banned.

The later historian Tacitus reconstructs his defence speech:

“Conscript Fathers, my words are brought to judgement—so guiltless am I of deeds! … You may sentence me to death, but then not only Brutus and Cassius will be remembered. I, too, shall not be forgotten.”

– Aulus Cremutius Cordus according to Tacitus, Annales 4.34-35

Episode III: The Age of Persecution

Why did the polytheist Ancient Romans persecute the followers of the new Jewish sect of “Christians” in the first three centuries AD”? How high was the price that Christians had to pay for casting away their ancient religious traditions for the belief in salvation through Jesus Christ? Did Roman Emperor Constantine end religious intolerance with the Edict of Milan? And why did the Christians persecute the pagans – and each other – once Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire? Why were temples and libraries destroyed and the female mathematician Hypatia killed by violent mobs? And did Emperor Justinian really end antiquity when he closed the Academy in Athens?

Find out when we discover how religious persecution and violence impacted lives, learning, and liberty of conscience in the period from the trial of Jesus to the age of Justinian. The Age of Persecution. That’s episode III of “Clear and Present Danger: A History of Free Speech”.

c. 30 AD: The trial of Jesus

The Deesis mosaic in Hagia Sophia dates from the 12th to 13th centuries (Photo: Edal Anton Lefterov)

In the early 30s AD, Jesus of Nazareth is arrested, tried and executed in Jerusalem. Within three decades, Christian communities have sprouted up in most cities of the Eastern Mediterranean.

64: The first persecution of Christians

The great fire according to Hubert Robert (1787) (Public Domain)

A devastating fire breaks out in Rome in 64 AD. According to the historian Tacitus, the Romans think Nero started the fire. To shift the blame, the Emperor accuses the Christians and opens the first in a long series of Christian persecutions. The victims are crucified, burned and fed to the dogs.

“… to scotch the rumour, Nero substituted as culprits, and punished with the utmost refinements of cruelty, a class of men, loathed for their vices, whom the crowd styled Christians … First, then, the confessed members of the sect were arrested; next, on their disclosures, vast numbers were convicted, not so much on the count of arson as for hatred of the human race. And derision accompanied their end: they were covered with wild beasts’ skins and torn to death by dogs; or they were fastened on crosses, and, when daylight failed were burned to serve as lamps by night.”

– Tacitus Annales 15.44