FREE SPEECH HISTORY TIMELINE

Dive into a timeline covering the subjects of Clear and Present Danger. The timeline will expand as we travel through the history of free speech.

Free speech history

1126-98: Ibn Rushd (Averröes)

Andrea Bonaiuto, Triunfo de Santo Tomás, fourteenth century.

Ibn Rushd, Latinized as Averroes, is one of the most influential thinkers of the Islamic Golden Age. The philosopher, jurist, and physician from Córdova is best known for his commentaries on Aristotle. He is persecuted by the sultan of Córdova in 1195, when the sultan needs orthodox support for his wars in Spain. But the draws back his edicts and Ibn Rushd can return to Marrakesh.

In his Decisive Treatise from 1198, Ibn Rushd argues that philosophy is mandated by the Qurʼān with it’s injunction to reflect on God’s design (59:2).

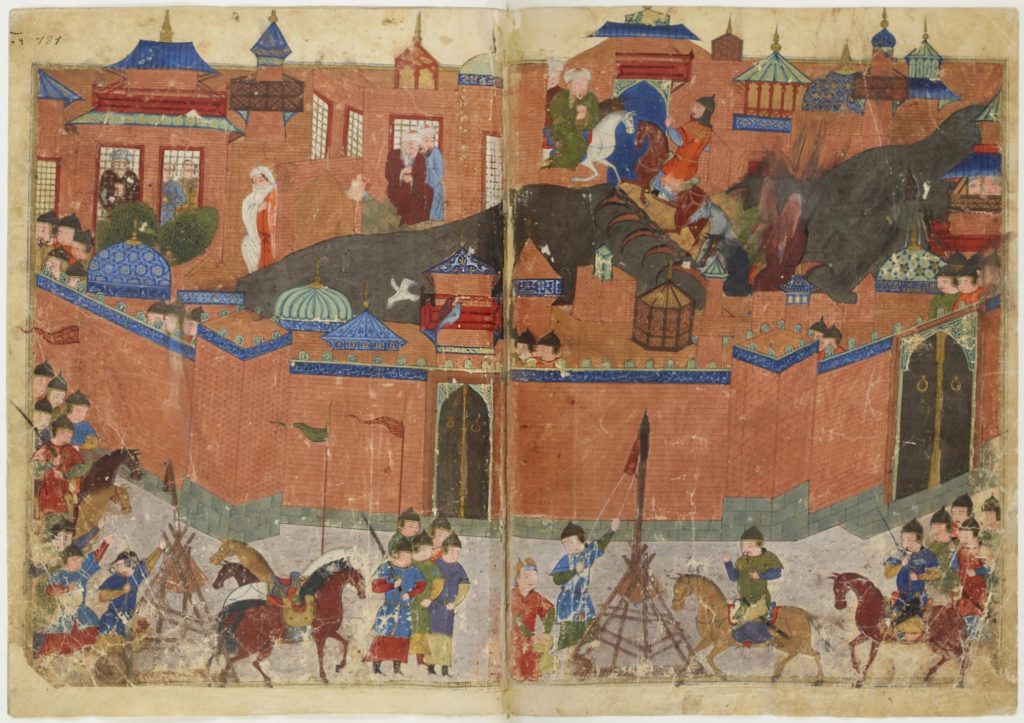

1258: The Fall of Baghdad

The Mongols besieging Baghdad, c. 1430, Bibliothèque nationale de France

The Mongols conquer Baghdad on January 29, 1258. The fall of Baghdad marks the fall of the ʿAbbāsid Caliphate and the Islamic Golden Age. Symbolically, the Tigris is said to run red with blood and black with ink.

Episode VI: The Not so Dark Ages

In episode VI, we get Medieval! Find out why the Middle Ages were as much a period of inquisition and persecution as reason and inquiry.

Why was the famous medieval intellectual Pierre Abelard castrated, forced to burn his works, and condemned to silence by the church? How did the combination of Aristotelian philosophy and the development of universities institutionalize reason and science? What are the parallels between clashes over academic freedom in the 13th and 21st centuries? All this and much more in “Clear and Present Danger” – episode VI!

800: Charlemagne

Pope Leo III crowning Charlemagne, 14th century illumination.

Charlemagne is another ambiguous character. After he becomes Holy Roman Emperor in 800, he revives the Latin language and rescues ancient manuscripts from oblivion. But he also makes blasphemy a capital crime and converts heathens by the sword.

“Ah, woe is me! that I was not thought worthy to see my Christian hands dabbling in the blood of those dog-headed fiends.”

– Charlemagne on the Scandinavian Vikings recorded by Notker the Stammerer in De Carolo Magno, 9th century.

1079-1142: Pierre Abelard

14th century miniature of Abelard and Héloïse (Public Domain)

The multitalented theologian, philosopher and poet Pierre Abelard (1079-1142) is most famous for the tragic love affair he has with his former student Héloïse. The affair quickly turns platonic when Abelard is castrated by Héloïse’s uncle.

But Abelard is also a radical freethinker whose writings attract a fair amount of controversy. In 1121, the synod in Soissons condemns Abelard’s work Theologia for heresy. Abelard is mandated to burn the book with his own hands. In 1141, Abelard’s heretical writings are condemned and burned for a second time. He lives out the last year of his life in a monastery.

Abelard dies in 1142. Always the skeptic, his dying words are supposedly “I don’t know”.

For Abelard,

“Constant and frequent questioning is the first key to wisdom … For through doubting we are led to inquire, and by inquiry we perceive the truth.”

– Abelard, prologue to Sic et Non (1120)

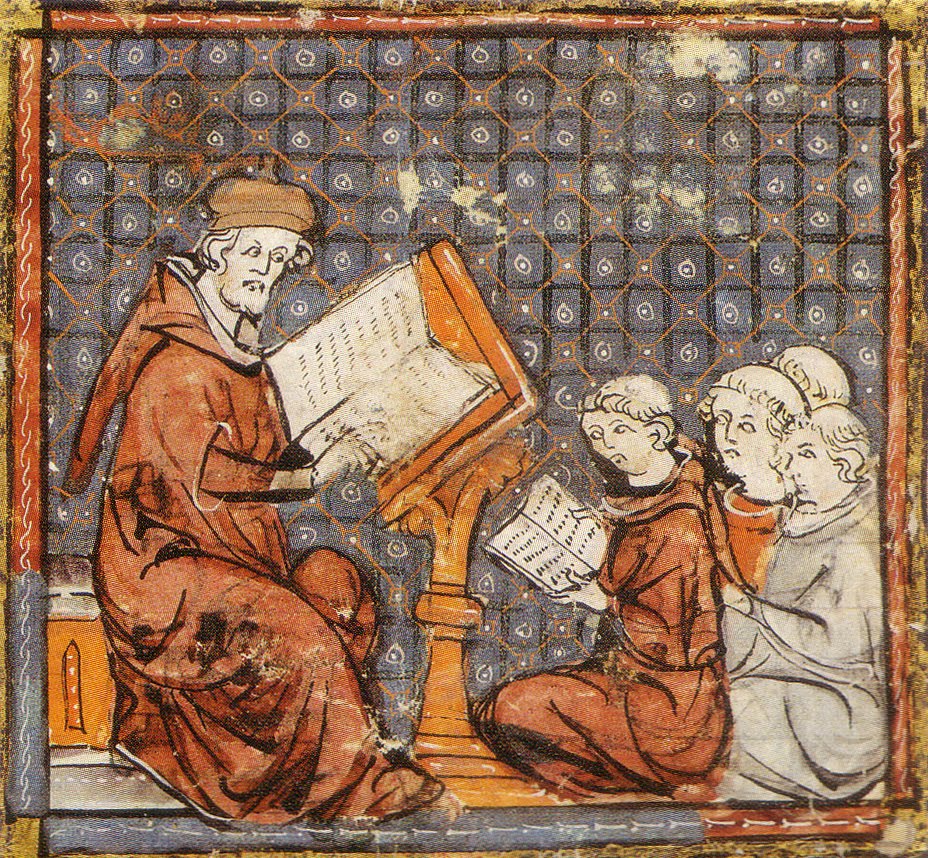

c. 1200: Birth of the European University

Europe’s first universities are born in Paris and Bologna around the year 1200 when masters and students form guilds known as universitas magistrorum et scholarium. A few years later, the first English universities evolve in Oxford and Cambridge. By 1300, Europe has 18 universities. By 1500, it has 70.

With the rise of the university, masters of theology assume the role of heresy police from the church. There are about 50 known cases of academically related heresy trials in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

The first victim is Master Amalric of Bène. Around 1206, he is found guilty of false teaching because of his pantheism. Four years later, he is excommunicated and his followers are burned at the stake outside the gates of Paris.

But the majority of cases convict books and not persons. Most offenders are free to continue their careers if they recant their views and burn the problematic books.

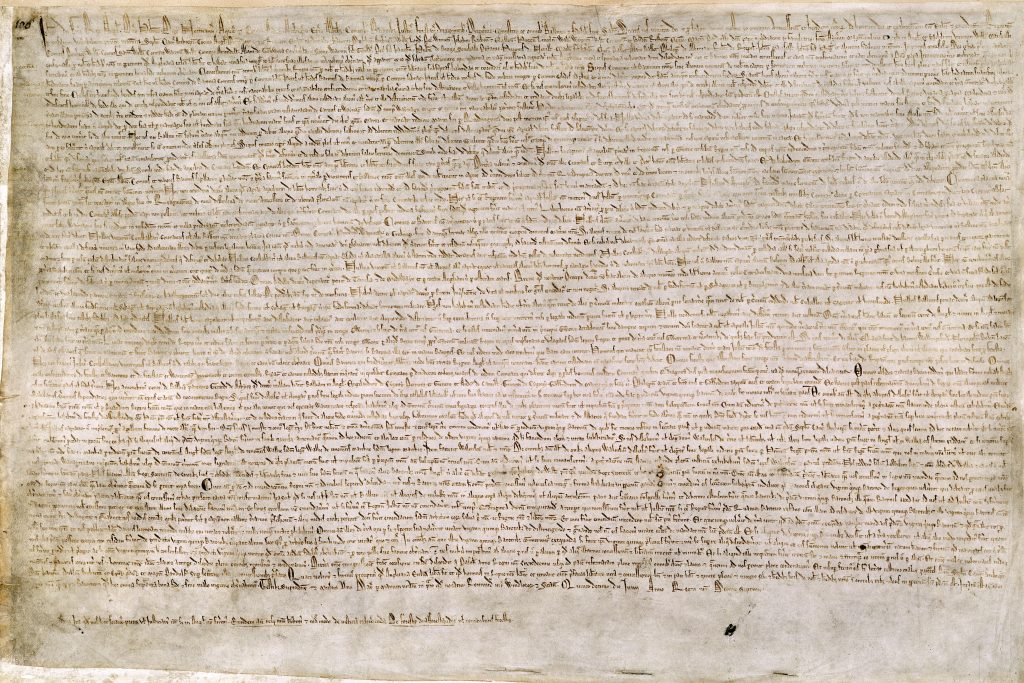

1215: Magna Carta

One of four surviving exemplifications of the lost original charter

The Magna Carta or ‘Great Charter’ is signed by King John in 1215 under pressure from the aristocracy. The document limits the power of the crown, restricts taxes, guarantees freedom of the church and promises justice for all. The Magna Carta is a cornerstone of British liberty.

1225–1274: Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas sitting between Plato (right) and Aristotle (left). Benozzo Gozzoli: Triumph of St. Thomas Aquinas, 1470-1475

Thomas Aquinas becomes one of the most influential thinkers in Medieval Europe when he reconciles Christian theology with ancient Greek philosophy. For instance, he uses principles from Aristotle to prove the existence of God.

In 1277, many of Aquinas’ propositions are condemned and banned by the Bishop of Paris.

Reason in man is rather like God in the world.

– Thomas Aquinas, Opuscule II, De Regno

1277: The Condemnations of Étienne Tempier

Giovanni di Paolo: St. Thomas Aquinas Confounding Averroës (1445-1450). Bishop Tempier mainly condemned the works of Aquinas and Averroës aka Ibn Rushd.

In March 1277, the Parisian bishop Étienne Tempier issues a list of 219 forbidden propositions. The list includes the notion that “happiness is found in this life, and not in another”. The Archbishop of Canterbury issues the same list.

Most of the condemned propositions revolve around the thoughts of Aristotle and Aristotelian philosophers like Thomas Aquinas, Siger of Brabant, Ibn Rushd (Averoës) and Ibn Sina (Avicenna).

C. 1287–1347: William of Ockham

The friar and philosopher William of Ockham is best known for his razor: The problem-solving principle of choosing the explanation based on fewest assumptions. In 1339 and 1340, two statutes ban Ockham’s ideas from the faculty of arts at the University of Paris.

‘Purely philosophical assertions which do not pertain to theology should not be solemnly condemned or forbidden by anyone, because in connection with such anyone at all ought to be free to say freely what pleases him.’

– William of Ockham, Dialogus vol. 1, bk. 2, ch. 22

1299-1369: Nicholas of Autrecourt

The philosopher Nicholas of Autrecourt – also known as the ‘Medieval Hume’ – is convicted of false teaching in 1346. He is sentenced to burn his works and stripped of his title as master of arts.

Episode VIII: The Hounds of God

From the High Middle Ages, Europe developed into a “persecuting society,” obsessed with stamping out the “cancer” of heresy. But questions about how this was accomplished — and the consequences of these developments — abound:

- Why did popes and secular rulers shift from persuasion to persecution of heretics?

- Why was human choice in matters of religious belief considered a mortal threat to Christendom itself?

- Why did bookish inquisitors armed with legal procedure, interrogation manuals, data and archives succeed where bloody crusades and mass slaughter failed?

- How did the “machinery of persecution” developed in the Late Middle Ages affect other minority groups such as Jews?

- Are inquisitions a thing of a past and dark hyper-religious age, or a timeless instrument with appeal to the “righteous mind” whether secular or religious?

- What are the similarities between medieval laws against heresy and modern laws against hate speech?

We try to answer these questions — and more — in episode 8 of Clear and Present Danger: The Hounds of God.

1184-1240: The Medieval Inquisition

The term ‘Medieval Inquisition’ covers series of inquisitions from 1184 to the 1230s.

Pope Lucius III opens the Episcopal Inquisition in 1184 to combat the heretical Cathars and Waldensians. Both groups are excommunicated, and the pope issues a bull to instruct his bishops to comb their jurisdictions for heretics twice every year.

Innocent III steps up the inquisition in 1199 and makes heresy a form of high treason. In 1208, the pope orders a crusade on the Cathars and between 10-15,000 are massacred in the town of Beziers.

In 1231, Pope Gregory IX orders Dominicans in the German city of Regensburg to “seek out diligently those who are heretics or are inflamed of heresy”. An increasing number of people are burned to death in the following decade.

1415: The execution of Jan Hus

Jan Hus at the stake. Spiezer Chronik, 1485

The Bohemian theologian Jan Hus is burned to death in Jena on July 6, 1415. The execution is a sign of times to come: The number of religious executions grow rapidly in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries.

But I rejoice that they were compelled to read my books, in which their wickedness was revealed. I know that they have perused these books more carefully than the Holy Scriptures in their desire to discover my errors.

– Jan Hus in a letter, nine days before his execution

1478: The Spanish Inquisition

Scene from an Inquisition by Francisco Goya, 1808-12

The Spanish Inquisition is initiated by Isabel of Castille and Fernando of Aragon in 1478. Around 150,000 are persecuted and 3-5,000 executed before the inquisition is called off in 1834.

1492: The Alhambra Decree

Spanish Jews pleading with Isabel, Fernando and grand inquisitor Tomás de Torquemada in a painting by Solomon A. Hart.

The Alhambra Decree issued by Fernando and Isabel expels all practising Jews from the Kingdoms of Castile and Aragon and their possessions. Also known as the Edict of Expulsion, it is issued on 31 March 1492 and effective from 31 July.

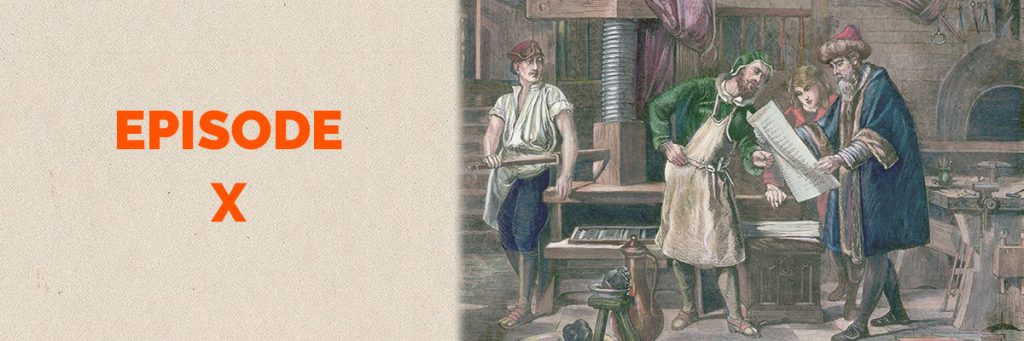

Episode X: The Great Disruption Part I

The disruptive effects of the internet and social media on the spread of information are unprecedented. Or are they?

In episode 10 of Clear and Present Danger, we cover the invention, spread, and effects of Gutenberg’s printing press:

- What significance did this new technology have for the dissemination of knowledge and ideas?

- Why was the printing press instrumental in helping a German monk and scholar break the religious unity of Europe?

- What happened when new religious ideas raged through Europe like wildfire?

- And did Martin Luther’s Reformation lead to religious tolerance and freedom, or persecution and censorship?

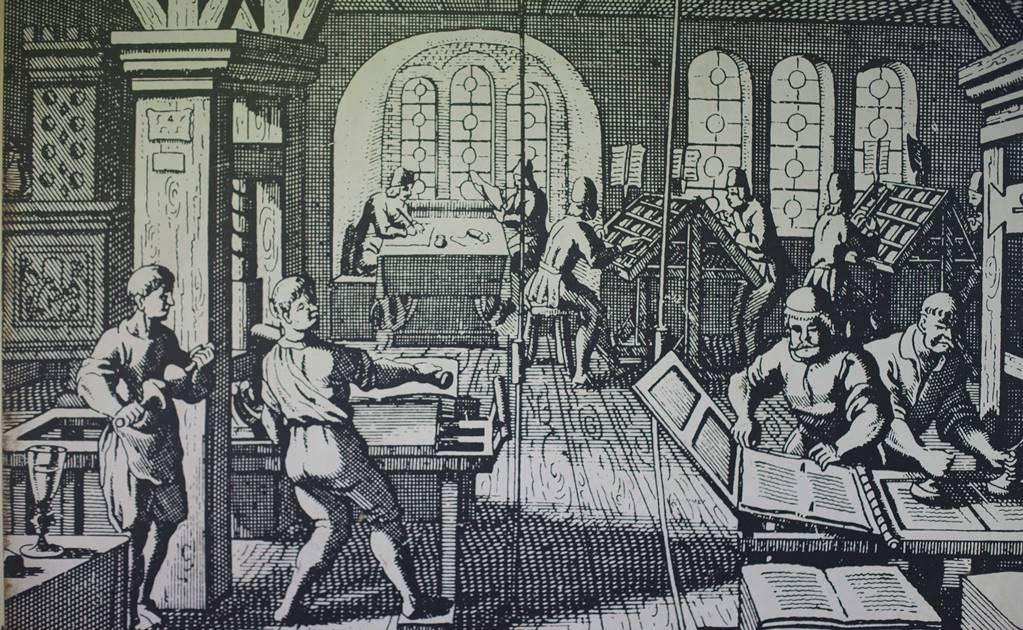

c. 1450: The Gutenberg Revolution

Woodcut of early printing workshop (Public Domain)

Around 1448, the German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg (c. 1400 – 1468) gets a brilliant idea: He takes a printing press and breaks reconstructs its printing surface into changable components. He sets up a print office in Mainz and prints his first Bible around 1454.

Gutenberg’s invention quickly goes viral. Before long, printing presses appear in Germany, Italy, France and the Low Countries. Then they crop up in Bohemia, Poland, England, Spain, Portugal, and Scandaniva. The number of operating printing presses in Europe rises from around 15 in 1471 to at least 87 in 1480.

The Gutenberg Revolution has a profound influence on cultural and intellectual movements like the Renaissance, the Reformation and the Scientific Revolution.

1486-7: First censorship of the press

In 1486, the Archbishop-elector of Mainz establishes a censorship commission for his archbishopric.

One year later, Pope Innocent VIII issues a bull, which makes pre-authorization necessary before a text can be printed in the archbishioric.