FREE SPEECH HISTORY TIMELINE

Dive into a timeline covering the subjects of Clear and Present Danger. The timeline will expand as we travel through the history of free speech.

Free speech history

177: The Persecution of Lugdunum

In 177 during the reign of Marcus Aurelius, a local persecution of Christians erupts in Lugdunum or present day Lyon.

The Christian historian Eusebius (263-339) later passes on a first hand account of the persecution.

250: The Persecution of Decius

Byzantine fresco of St Mercurius, a victim of Decius’ persecution (1295) (Public Domain)

The Roman Emperor Decius begins the first general persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire in 250. The persecution is an attempt to retrieve the favour of the gods in the great crisis of the 3rd century. All subjects of the Empire are ordered to sacrifice to the old gods on pain of death.

303: The Great Persecution

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1883): The Christian Matyrs’ Last Prayer (Public Domain)

The emperor Diocletian launches ‘The Great Persecution’ in the winter of 303. Edicts prohibit Christians from meeting and Bibles are burnt in public. Next year, all subjects are ordered to sacrifice on pain of death. According to estimates of modern historians, between 2,500 and 3,500 are killed in the persecution.

311-337: The Edicts of Toleration

Raphael (1517-24): The Baptism of Constantin (Public Domain)

The emperor Galerius puts a stop to the Christian persecutions in 311 by issuing the Edict of Toleration. Two years later, his successor Constantin declares freedom of religion with his Edict of Milan. Read both edicts here. Constantin becomes the first Christian emperor of Rome when he is baptised on his deathbed in 337.

“… no one whatsoever should be denied the opportunity to give his heart to the observance of the Christian religion, of that religion which he should think best for himself…”

– Constantin, The Edict of Milan

380: Christianity becomes the state religion of Rome

The emperor Theodosius I (r. 379-95) makes Christianity the official state religion of the Roman Empire in 380. More pagans and heretics are persecuted. The same year, the emperor issues the Theodosian Code:

“It is Our will that the people who are ruled by the administration of Our Clemency shall practice that religion which the divine Peter the apostle transmitted to the Romans… The rest, however, whom We adjudge demented and insane, shall sustain the infamy of heretical dogmas, their meeting places shall not receive the name of churches, and they shall be smitten first by divine vengeance and secondly by the retribution of Our own initiative, which We shall assume in accordance with the divine judgment.”

– Theodosian Code, 380 AD

415: Death of Hypatia

During Lent of 415, a Christian mob attacks the Alexandrian philosopher and mathematician Hypatia. The Christians drag her through the streets to a local church. According to one account, they strip her naked and use broken tiles to cut the flesh off her body. Her mutilated remains are paraded through the city.

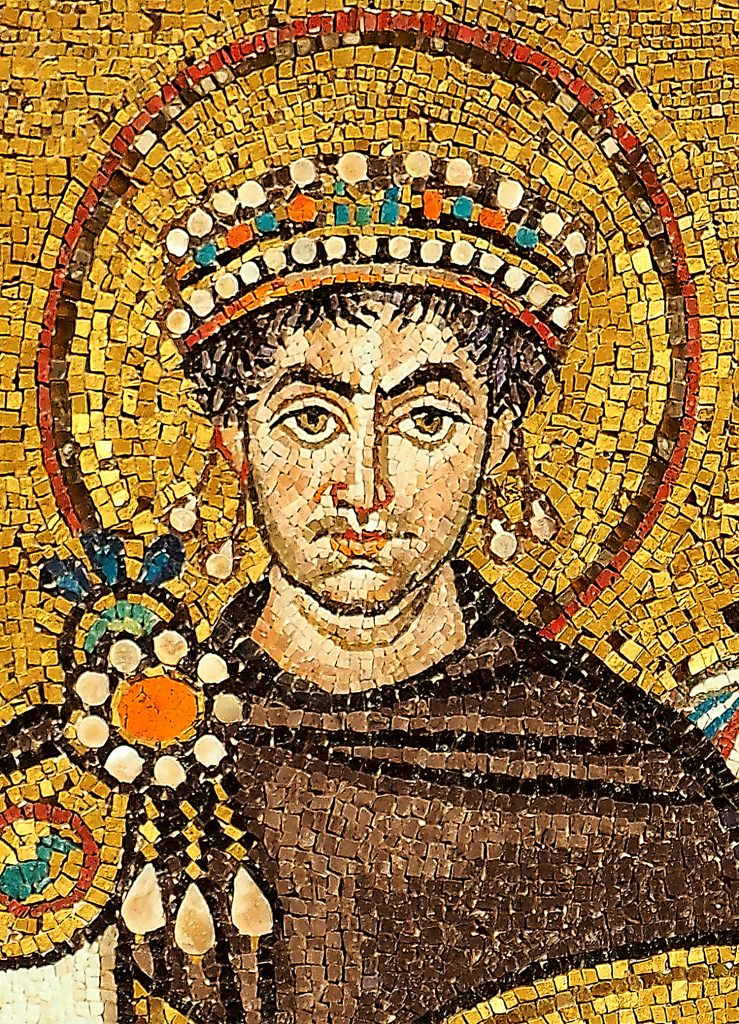

527-65: Justitian I

Mosaic in Ravenna (Public Domain)

Justinian I (r. 527-565) rules his empire according to the motto “One empire, one faith, one church”. In 529, he closes the ‘pagan’ Neoplatonic Academy in Athens. In 529 and 531, he bans all heretics – including pagans and non-orthodox Christians – from becoming teachers. In 539 he introduces the death penalty for blasphemy, lest “God in his wrath may destroy the cities and their inhabitants”.

Episode V: The Caliphate

Why did the medieval ʿAbbāsid Caliphs have almost all ancient Greek works of philosophy and science translated into Arabic? How did the long list of medieval Muslim polymaths reconcile abstract reasoning with Islamic doctrine?

Who were the radical freethinkers that rejected revealed religion in favor of reason in a society where apostasy and heresy were punishable by death?

And why are developments in the 11th century crucial to understanding modern controversies over blasphemy and apostasy, such as the Salman Rushdie affair and the attack on Charlie Hebdo? Find out in episode V of “Clear and Present Danger: A History of Free Speech”.

C. 622-632: Muhammad and the rise of Islam

Muhammad al-Idrisi’s map of the world (1154) (Public Domain)

Muhammad (c. 570-632) is the founder of Islam and proclaimer of the Qur’ān. According to Islamic tradition, he receives his first revelations in the 610’s. With his followers, he conquers much of the Arabian Peninsula until he dies in Medina in 632.

After his death, the First Caliphate conquers the Middle East and North Africa at break neck speed. Within thirty years, the Caliphate stretches from Gibraltar to Persia.

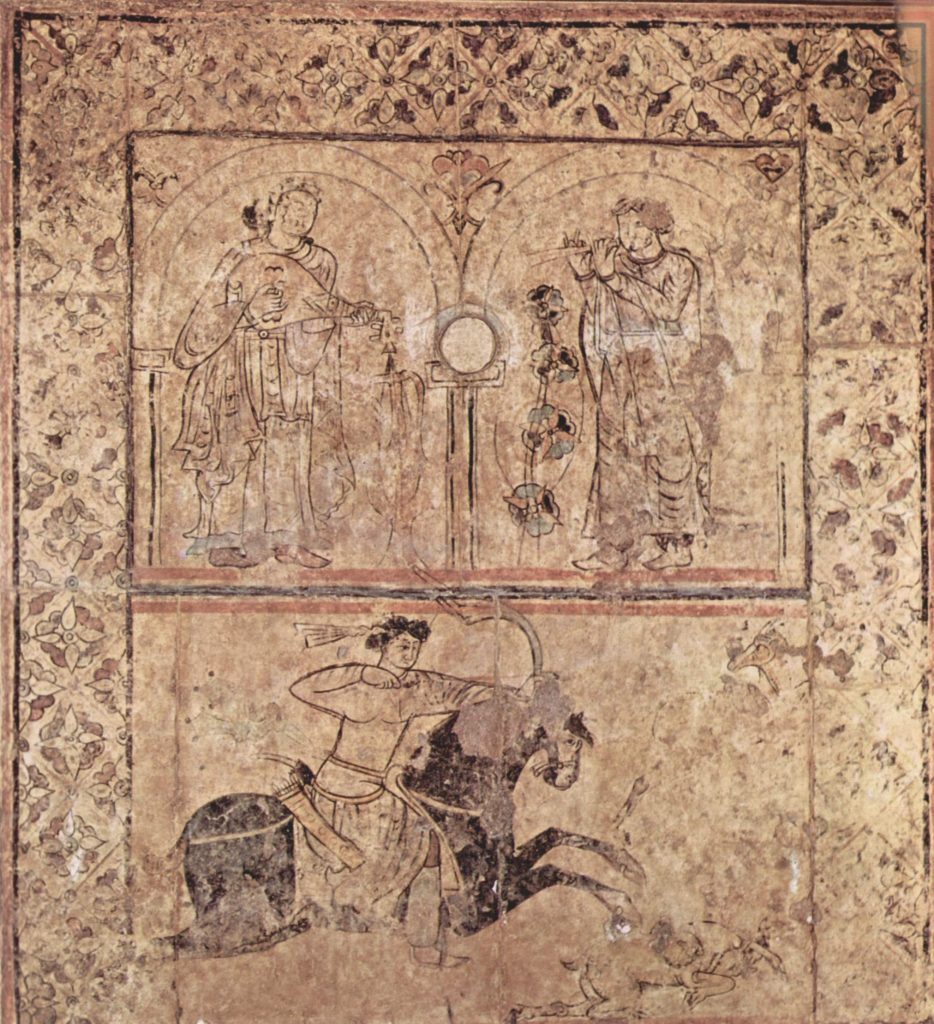

661-750: The Umayyad Caliphate

Floor painting in Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi built by Ummayad Caliph HishāmʿAbd al-Malik (Public Domain)

The Umayyads rules the Caliphate from their capital in Damascus between 661 and 750. The dynasty expands the Caliphate as far as the Indus river.

Around 684, Caliph ʿAbd al-Malik makes one of the first attempts to purge the Caliphate from heresy. The believe in free will is especially dangerous because it is believed to undermine the legitimacy of the caliphs. One heretic is crucified around 699.

The religious scholar Dirham is executed for heresy by the Caliph HishāmʿAbd al-Malik in 724.

750-1258: The ‘Abbāsids and the Islamic Golden Age

The ‘Abbāsid Dynasty rules the Caliphate from their capital in Baghdad for five centuries. The Dynasty initiates what is known as ‘The Islamic Golden Age’: A time of great social, scientific and philosophical progress.

754: The Graeco-Arabic translation movement

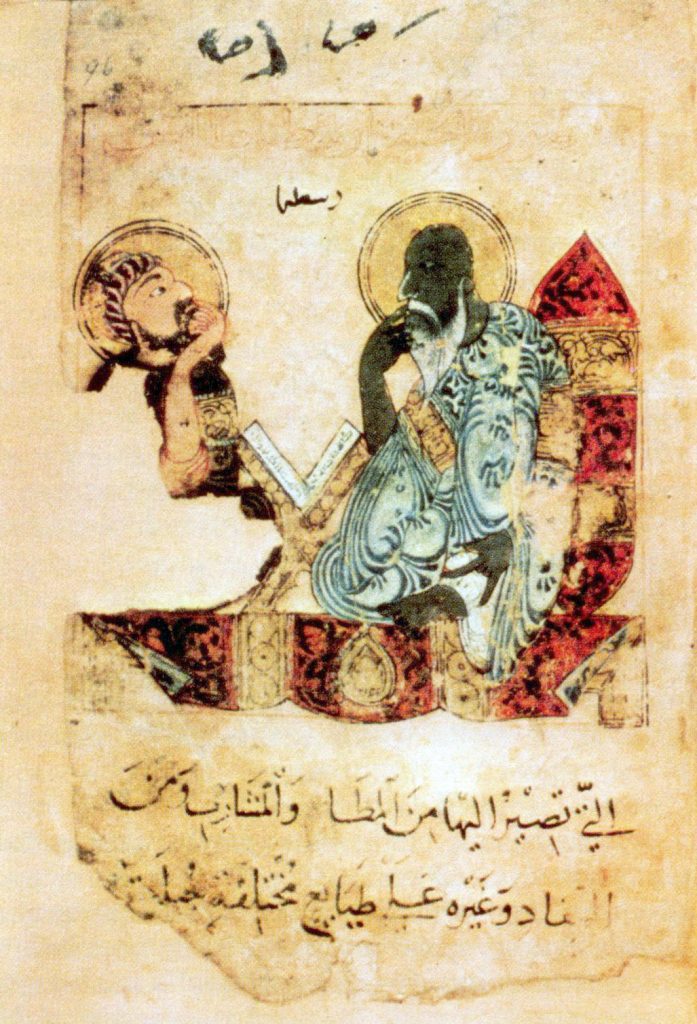

Aristotle depicted in the Kitāb naʿt al-hayawān manuscript (9th century)

The Graeco-Arabic translation movement is launched by Caliph Al-Mansur in 754. In the following centuries, ancient thinkers like Aristotle, Plato, Ptolemy, Euclid, Galen and Hippocrates are translated from Greek to Arabic.

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the ancient thinkers are translated from Arabic to Latin. From the Islamic world, the ancient ideas seep into the European universities and influence European scholars.

868: The world’s first printed book

The Chinese Wang Jie prints the Diamond Sutra in 868. This is the first printed book in recorded history.

833-848: The Mihna

al-Maʾmūn (depicted left), the Madrid Skylitzes

The ʿAbbāsid Caliph al-Maʾmūn institutes a religious persecution known as the Mihna in 833. Scholars are imprisoned, flogged and even executed if they refuse to conform to the Muʿtazila doctrine and believe the Qurʾān is uncreated and co-eternal with God.

The persecution is called off 15 years later by the Caliph al-Mutawakkil. The Minha is one of the few instances of specifically religious persecution in Medieval Islam.

827-911: Ibn al-Rawandi

Ibn Al-Rawandi of Khorasan in present day Afghanistan is one of the earliest Islamic sceptics. None of his 114 books have survived, but he is often cited by his many critics in their furious refutations.

During his lifetime, Al-Rawandi jumps from Mutazilite to Shīʿite to radical scepticism bordering on atheism. Disguised in the voices of Indian Brahmins, his works reject miracles, attack the Qurʾān as an absurd book full of inconsistencies and holds that prophets are unnecessary and fraudulent. Even the prophet!

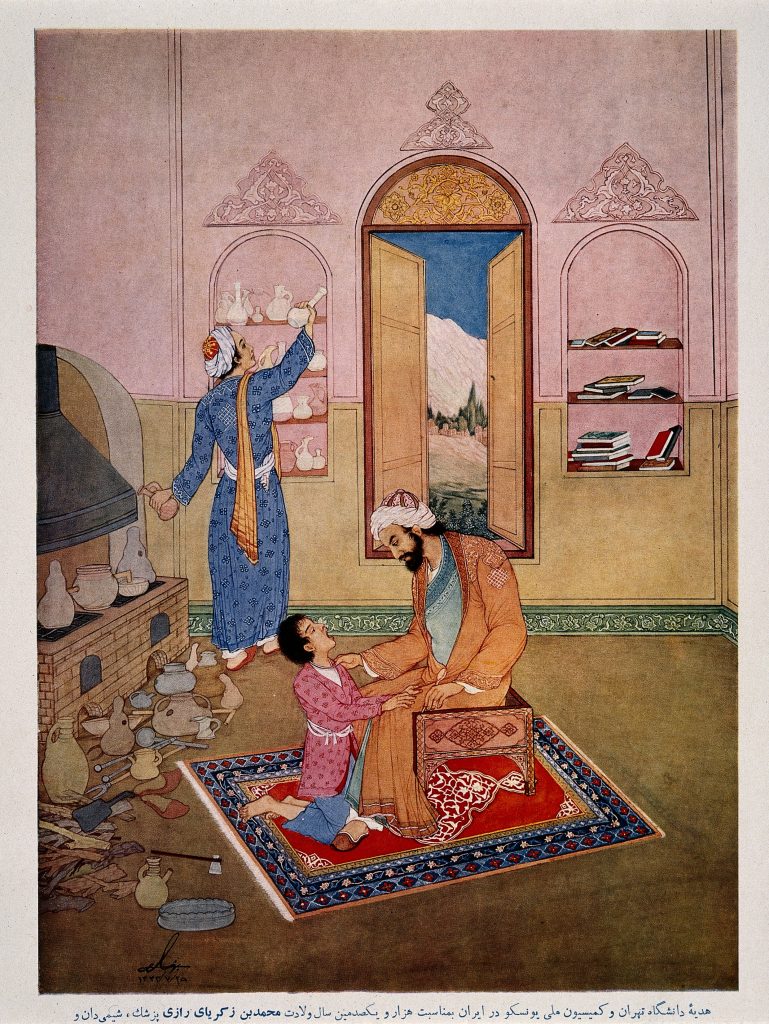

854-c.925: al-Rāzī

al-Rāzī examining a sick boy (Color print after Hossein Behzad)

The nearly 200 books of Persian multi talent Abū Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariyyā al-Rāzī – also known as ‘Rhazes’ – span everything from medicine and chemistry to logic and philosophy. He supposedly goes blind from all the reading and writing. His greatest achievements include the discovery of alcohol and a groundbreaking thesis on measles and smallpox.

As a religious freethinker, his criticism of revelation and the Qurʾān leads to multiple accusations of heresy. For al-Rāzī:

“Reason is the ultimate authority, which should govern and not be governed; should control and not be controlled, should lead and not be led.” – al-Rāzī

c.870-951: al-Fārābī

al-Fārābī’s portrait on a Kazakh banknote (Public Domain)

Abu Nasr al-Fārābī is known as ‘the second teacher’, after Aristotle. The philosopher from Thurkestan is one of the first thinkers to synthesize Aristotle and Plato with Islamic theology. Thanks to al-Fārābī, ancient Western philosophy becomes a vital part of the Islamic world for the next three centuries.

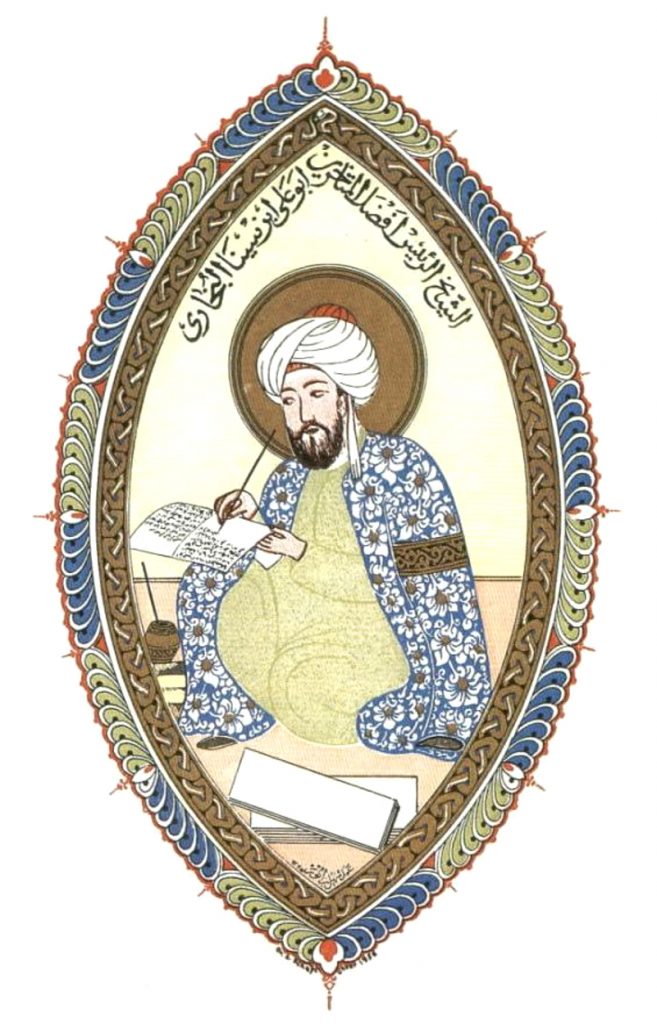

980-1037: Ibn Sina (Avicenna)

Ibn Sina, Latinized as Avicenna, is the most influential thinker of the Islamic Golden Age. The philosopher and physician from Bukhara refines al-Fārābī’s synthesis of Aristotle and Plato with Islamic theology. The succesful attempt has a tremendous impact on Muslim, Jewish and Western philosophers like Thomas Aquinas, who finds his own synthesis between Aristotle and Christian theology.

1058-1111: al-Ghazālī

Al-Ghazālī in Arabic calligraphy

The influential thinker al-Ghazālī dissects the arguments of Ibn Sina, al-Farabi and other thinkers who try to synthesize Aristotle with Islamic theoloy. He identifies three propositions so problematic that their advocates should be executed without chance to repent: The notions that the world was not created, that God is not omniscient, and that the rewards and punishments in the next life are only spiritual in character. Al-Ghazālī is often depicted as a strict opponent to reason, but modern scholars think he has been slightly misinterpreted.