FREE SPEECH HISTORY TIMELINE

Dive into a timeline covering the subjects of Clear and Present Danger. The timeline will expand as we travel through the history of free speech.

Free speech history

1683: Execution of Algernon Sidney

Algernon Sidney writes his radically anti-monarchical Discourses Concerning Government during the Exclusion Crisis of 1679-81. It is published posthumously in 1698 and has a tremendous influence on the radical Whigs and the founding fathers of America.

Sidney is executed for an alleged plot against Charles II in 1683. Just before the execution, he delivers a speech on the scaffold:

“… we live in an age that maketh truth pass for treason; I dare not say anything contrary unto it, and the ears of those that are about me will probably be found too tender to hear it. My trial and condemnation sufficiently evidence this.”

– Algernon Sidney on the scaffold

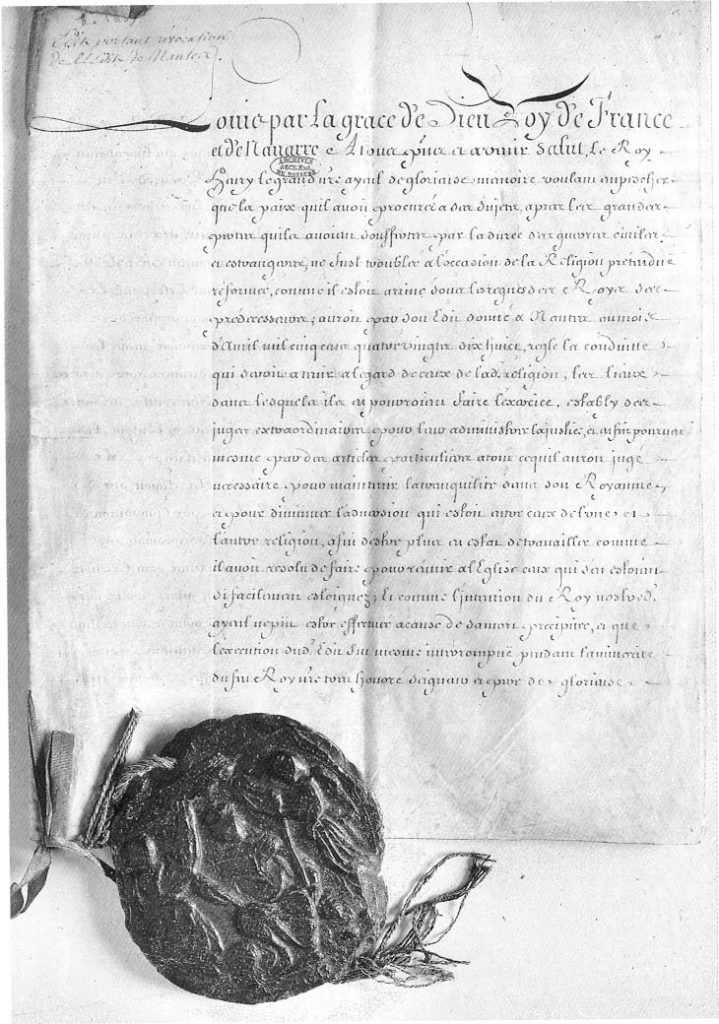

1685: The Edict of Fontainebleau

Edict of Fontainebleau © Archives Nationales

The Edict of Fontainebleau is issued by Louis XIV in October 1685. The edict revokes the Edict of Nantes from 1598 and suspends the religious freedom of French protestants. Tens of thousands of protestants migrate to countries like England, the Dutch Republic and the American colonies.

“we have determined that we can do nothing better, in order wholly to obliterate the memory of the troubles, the confusion, and the evils which the progress of this false religion has caused in this kingdom, and which furnished occasion for the said edict and for so many previous and subsequent edicts and declarations, than entirely to revoke the said Edict of Nantes, with the special articles granted as a sequel to it, as well as all that has since been done in favor of the said religion.”

– The Edict of Fontainebleau (1685)

Read the full document here.

1687: The Declaration of Indulgence

King James II. Portrait by Peter Lely, c. 1650-1675 (Public Domain)

The Declaration of Indulgence is issued by the Catholic James II in early 1987. It is issued in Scotland in February and England in April. Also known as the Declaration for Liberty of Conscience, it grants religious freedom for minorities like Catholics, Protestant dissenters, Unitarians, Jews and Muslims. It also suspends the discriminatory penal laws and revokes the required Protestant oaths in civil and military offices. The declaration marks the first step towards religious freedom in Britain, even if the king explicitly wants to promote his own religion.

“It having pleased Almighty God not only to bring us to the imperial crown of these kingdoms through the greatest difficulties, but to preserve us by a more than ordinary providence upon the throne of our royal ancestors, there is nothing now that we so earnestly desire as to establish our government on such a foundation as may make our subjects happy, and unite them to us by inclination as well as duty; which we think can be done by no means so effectually as by granting to them the free exercise of their religion for the time to come, and add that to the perfect enjoyment of their property, which has never been in any case invaded by us since our coming to the crown; which being the two things men value most, shall ever be preserved in these kingdoms, during our reign over them, as the truest methods of their peace and our glory.”

– King James II, The Declaration of Indulgence, April 1687

Read the full document here.

1689: The Toleration Act and the Bill of Rights

William III and his co-ruler Mary II. Portrait by Sir James Thornhill (Public Domain).

The Dutch William of Orange invades Britain and takes the British throne in the Glorious Revolution of late 1688.

One of the first deeds of William III and his queen Mary II is the Toleration Act of May 1689. The law grants religious freedom to most Protestant dissenters, but not to Catholics, anti-Trinitarians and Atheists.

In December, the regents give royal assent to the Bill of Rights, which secures freedoms like habeas corpus and free speech in parliament:

9. That the freedom of speech, and debates or proceedings in parliament, ought not to be impeached or questioned in any court or place out of parliament.

– The Bill of Rights (1689)

Read the Bill of Rights here.

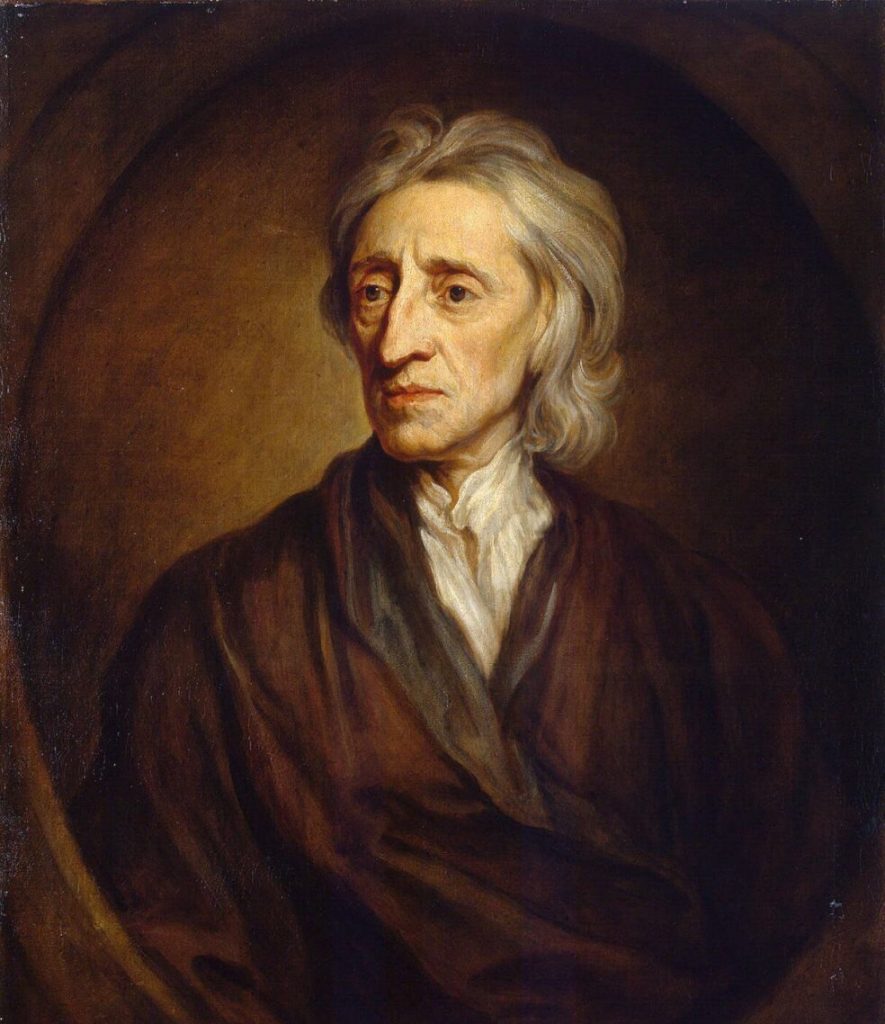

1689: John Locke’s Letter on Toleration

Portrait by Godfrey Kneller, 1697 (Public Domain)

John Locke pens his Epistola de tolerantia or Letter on Toleration in 1685, during his exile in Gouda. The text is published in Latin and English in 1689.

By the law of nature, he argues, all men have the right – and duty – to worship God in religious communities of their own choosing:

“Now I appeal to the consciences of those that persecute, torment, destroy, and kill other men upon pretense of religion, whether they do it out of friendship and kindness towards them, or no … I say, if all this be done merely to make men Christians, and procure their salvation, why then do they suffer whoredom, fraud, malice, and such like enormities, which, according to the Apostle, manifestly relish of heathenish corruption, to predominate so much and abound amongst their flocks and people?”

– John Locke, Epistola de tolerantia (1689)

But Locke is not a promoter of universal toleration. He draws the limit at Roman Catholicism and Atheism:

“… those are not at all to be tolerated who deny the being of a God.”

– John Locke, Epistola de tolerantia (1689)

1695: Locke and the end of the Licensing Act

The Licensing Act expires in 1695. No longer does it enforce pre-publication censorship and ban ‘heretical, seditious, schismatical, or offensive books’.

John Locke plays a critical role lobbying against the law. Not to argue for a free press, but because the monopoly of the Stationers’ Company drives prices of books up and quality down, and because the law violates property rights by allowing authorities ‘to search all houses [on] the suspition of haveing unlicensed books’.

“I know not why a man should not have liberty to print whatever he would speak; and to be answerable for the one, just as he is for the other, if he transgresses the law in either. But gagging a man, for fear he should talk heresy or sedition, has no other ground than such as will make chains necessary, for fear a man should use violence if his hands were free, and must at last end in the imprisonment of all who you will suspect may be guilty of treason or misdemeanor”

– John Locke on the Licensing Act

The end of the Licensing Act causes an explosion of heterodox, anti-Trinitarian pamphlets. It also allows British Catholics to publish their catechisms and prayer books uncensored.

Episode XXI: The Bulwarck of Liberty

18th century America was impacted and influenced by the so-called Glorious Revolution in the Motherland. And no-one had a bigger impact on American attitudes towards freedom of speech than Cato’s Letters written by the Radical Whigs John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon. Cato’s Letters created a powerful free speech meme, that went viral in the colonies: “Freedom of Speech is the great Bulwark of Liberty”. The reach of Cato’s principles grew exponentially as colonists liked, shared and commented on them in newspapers, pamphlets and taverns. Americans were persuaded that “Without freedom of thought, there can be no such thing as wisdom; and no such thing as publick liberty, without freedom of speech: Which is the right of every man”. As a consequence, grand juries and juries refused to indict and convict colonists for seditious libel when criticizing governments and officials.

Despite the practical defeat of libels laws in colonial courts, legislative assemblies continued to threaten free speech. Under legislative privilege provocative writers could be jailed and fined by their own representatives. And even American heroes were sometimes willing to sacrifice principle.

In this episode we’ll explore:

- How coffee-houses expanded the public sphere by cultivating the sharing of news and ideas, including revolutionary ones.

- How the common law crime of seditious libel impacted writers

- How English writers including Matthew Tindal, John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon paved the way for American ideas on free speech

- How the editor of the New England Courant in Boston combined anti-vaxxer propaganda with free speech advocacy

- How the 16-year old Benjamin Franklin used Cato’s Letters to argue for freedom of speech when his brother James was in jail

- How the New York Weekly Journal became America’s first opposition newspaper and justified its savage hit pieces on New York governor William Cosby with Cato’s free speech principles

- How a jury acquitted the printer of the New York Weekly Journal Peter Zenger, even though he was guilty according to the law

- How legislative privilege was used to punish colonialists for offending their own representatives

- How Benjamin Franklin defended legislative privilege and the jailing of a Pennsylvania man for his writings

1735: The Zenger Trial

(Photo: Bettmann / Getty Images)

In 1734 the poor printer John Peter Zenger is jailed and charged with printing libellous criticism of New York’s governor. His lawyer, Andrew Hamilton, convinces the jury that the criticism is true, and that “truth ought to govern the whole affair of libels”. Zenger walks out a free man in August 1735.

“The loss of liberty in general would soon follow the suppression of the liberty of the press; for it is an essential branch of liberty, so perhaps it is the best preservative of the whole. Even a restraint of the press would have a fatal influence. No nation ancient or modern has ever lost the liberty of freely speaking, writing or publishing their sentiments, but forthwith lost their liberty in general and became slaves”

– Andrew Hamilton, lawyer, 1733

Episode XXII: Fighting Words

In the second half of the 18th century, American Patriots show that freedom of the press is a potent weapon against authority. Not even the world’s most formidable empire can stop them from speaking truth, lies, and insults to power.

In 1765, the announcement of the Stamp Act kicks off a tsunami of dissent in Colonial pamphlets, newspapers, taverns, and town meetings. The outpouring of protest shapes a public opinion increasingly hostile to taxation without representation and in favour of popular sovereignty. Additional taxes and disabilities imposed by Parliament further radicalizes the Patriot side and the anti-British propaganda. The revolutionary dissent includes both principled arguments, pamphlet wars, slander, and some genuine “fake news.”

Since prosecutions for seditious libel have effectively been abolished by the Zenger case in 1735 (see episode 21), the British are powerless to stop the onslaught of Patriot fighting words. More than ever, press freedom has become the “Great Bulwark of Liberty.”

Though Patriots constantly invokes the principle of freedom of speech, Loyalist printers and newspapers are subjected to the “Patriot’s Veto” through intimidation and mob violence.

Thomas Paine’s pamphlet “Common Sense” becomes a sensation and pushes many Patriot fence-sitters into the independence camp. And just before and after the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, several states protects freedom of the press in rights declarations.

1742: David Hume’s ‘Essays Moral, Political and Literary’

Portrait by Allan Ramsay, c. 1754 (Public Domain)

Hume’s Essays Moral, Political and Literary from 1742 contain a philosophical argument for freedom of the press:

“But I would fain go a step further and assert that such a liberty is attended with so few inconveniences that it may be claimed as the common right of mankind …”

– David Hume, Essays Moral, Political and Literary, 1742

In 1770, the Scottish philosopher has changed his mind. The argument is erased from the following editions of the essays. Instead, the “unbounded liberty of the press” is “one of the evils” associated with mixed forms of government. The American patriots ignore Hume’s backpedaling and an early unedited version of the essay circulates widely in the American press under the title “the celebrated Mr. Hume’s Observations on the Liberty of the Press”.

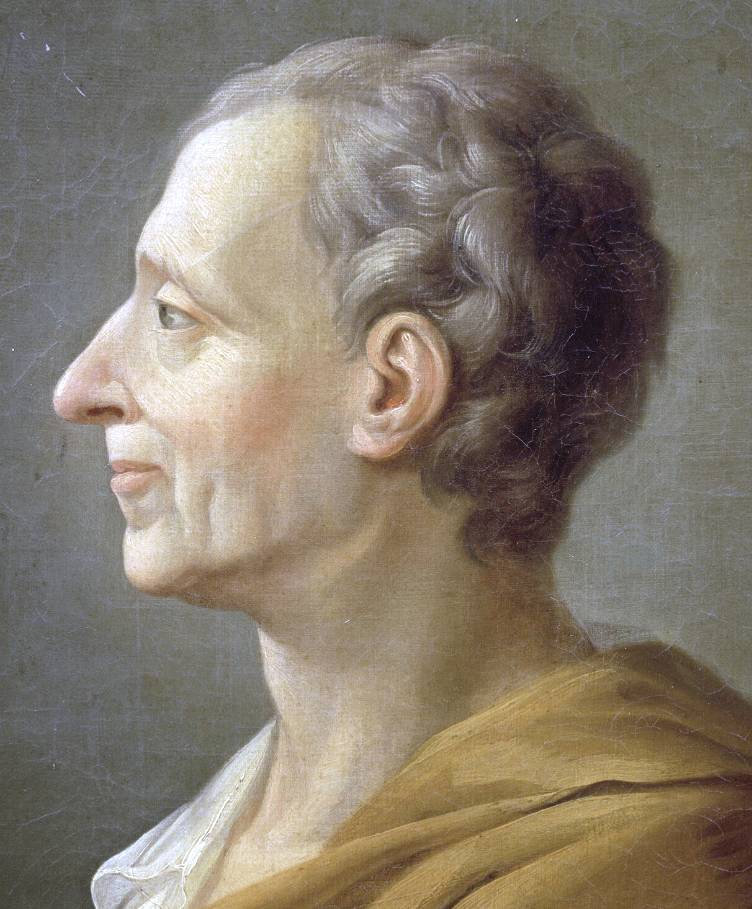

1748: Montesquieu and Spirit of the Law

J.-A. Dassier, Portrait of Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu (Public Domain)

Montesquieu’s De L’Esprit de Lois or Spirit of the Law from 1748 contains an argument for free speech and a seperation of words from actions:

“Words do not constitute an overt act; they remain only in idea … Since there can be nothing so equivocal and ambiguous as all this, how is it possible to convert it into a crime of high treason? Wherever this law is established, there is an end not only of liberty, but even of its very shadow …”

– Montesquieu, De L’Espirit de Lois (1748) bk. 12 ch. 12-13

Montesquieu has a tremendous influence on the founding fathers.

1775-1783: The American Revolutionary War

In 1775, a growing tension over political rights and taxation prompts Britain’s American colonies to rebel. Next year, the colonies declare their independence. The war ends in 1783 when the British sign the Treaty of Paris, formally recognising the sovereignty of the United States.

“If the freedom of speech is taken away then dumb and silent we may be led, like sheep to the slaughter.”

– George Washington to a group of military officers, 1783

1776: Thomas Paine’s Common Sense

Portrait by Laurent Dabos, c. 1792 (Public Domain)

In early 1776, the anonymous pamphlet Common Sense takes America by storm. The author Thomas Paine makes a merciless case for separation from the British empire. According to Paine’s own claims, it sells as many as 500,000 within the first year. Some historians think the actual number is closer to 75,000. But regardless, the pamphlet has a tremendous effect on the popular opinion on the separation question.

The pamphlet also makes a case for religious freedom:

“As to religion, I hold it to be the indispensible duty of every government, to protect all conscientious professors thereof, and I know of no other business which government hath to do therewith… For myself, I fully and conscientiously believe, that it is the will of the Almighty, that there should be a diversity of religious opinions among us …”

– Thomas Paine: Common Sense (1776)

1776: United States Declaration of Independence

(Photo: Tetra Images/Getty Images/Tetra Images RF)

The colonies formally declare their independence on July 4th, 1776.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

– United States Declaration of Independence (July 4, 1776)

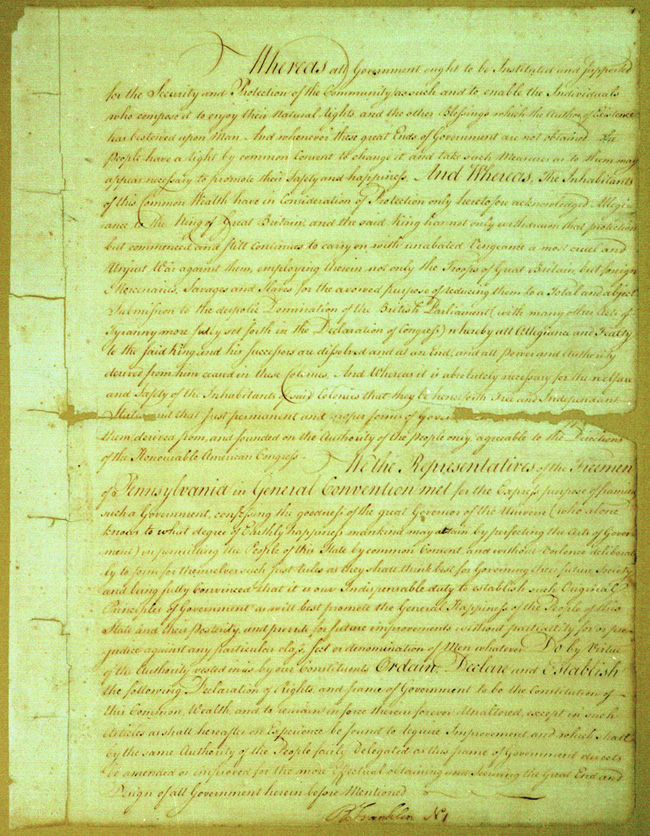

1776: The Pennsylvania Constitution

First page of the Pennsylvania Constitution (Public Domain)

Pennsylvania is the first state in America to declare freedom of speech, press and religion to constitutional rights. The Pennsylvania Constitution of September 1776 states:

“II. That all men have a natural and unalienable right to worship Almighty God according to the dictates of their own consciences and understanding … And that no authority can or ought to be vested in, or assumed by any power whatever, that shall in any case interfere with, or in any manner controul, the right of conscience in the free exercise of religious worship.”

“XII. That the people have a right to freedom of speech, and of writing, and publishing their sentiments; therefore the freedom of the press ought not to be restrained.”

– The Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776

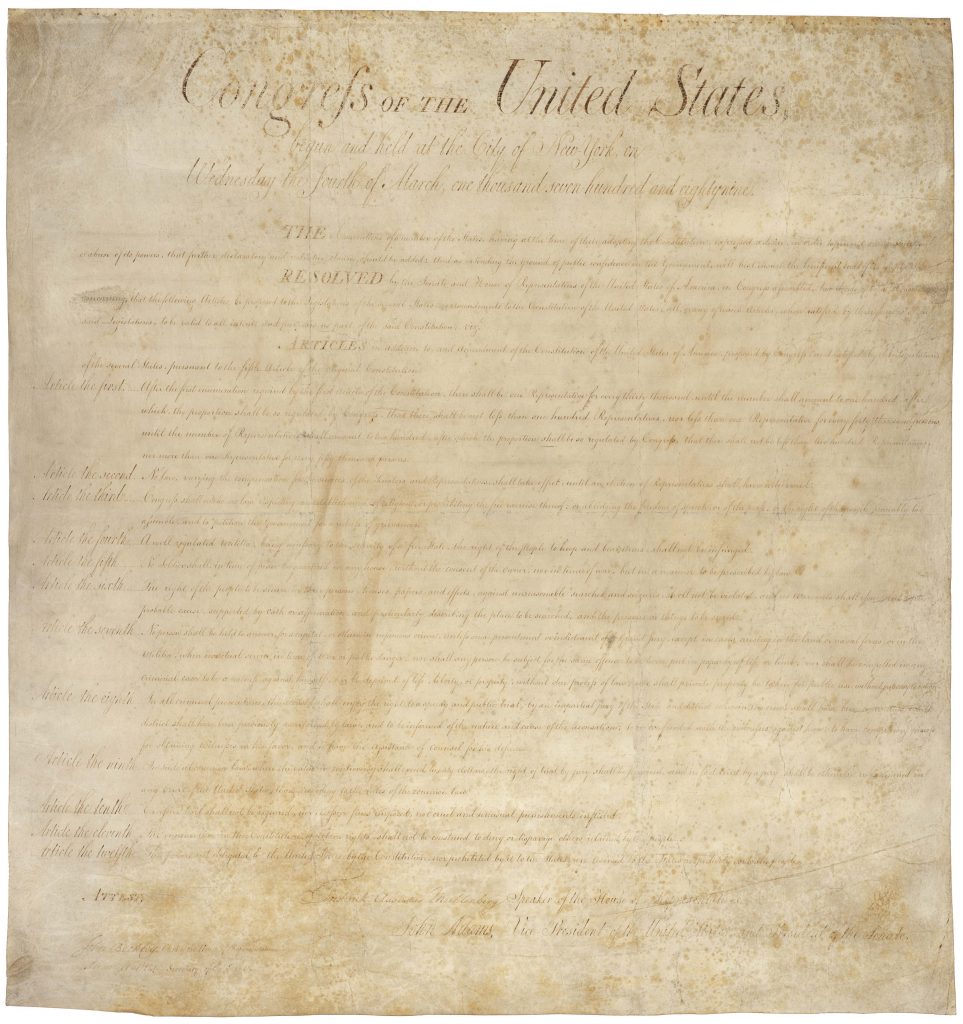

1791: The Bill of Rights

The First Amendment of the US Bill of Rights from 1791 guarantees freedom of speech, the press and religion.

‘Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.’

– US Bill of Rights, 1791

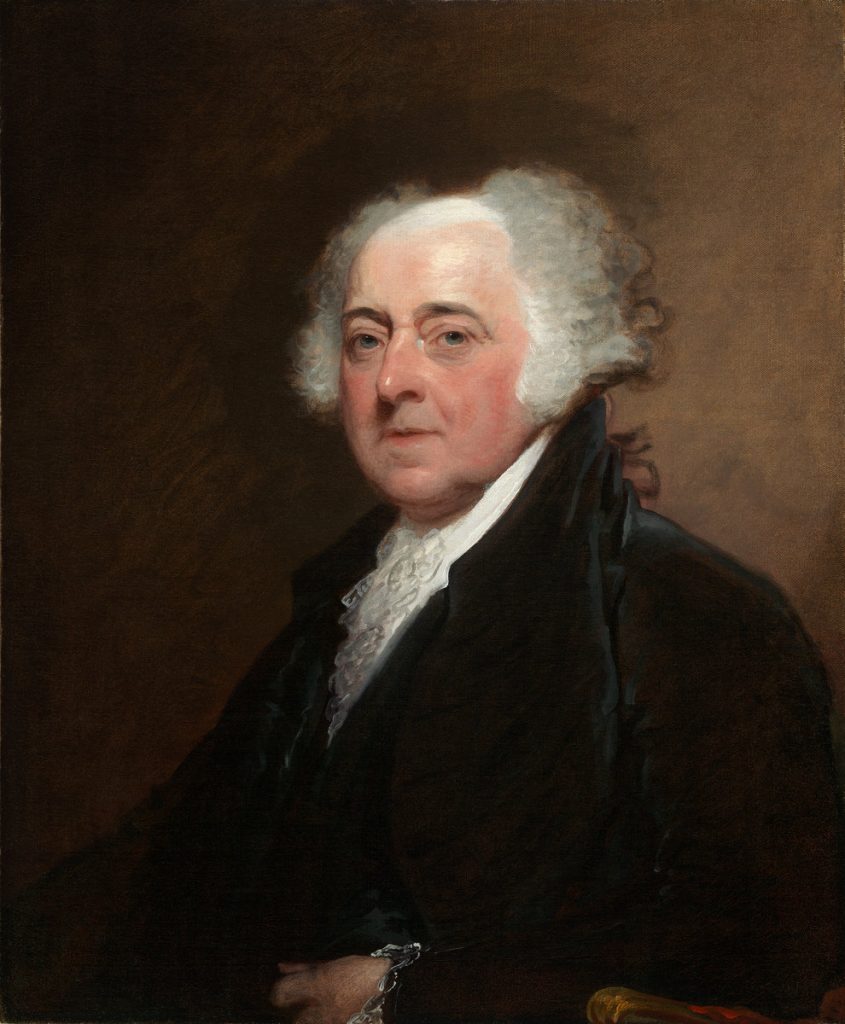

1798: The Sedition Act

President John Adams pushes the Sedition Act through in 1798, restricting criticism of the president to silence Thomas Jefferson’s supporters. When Adams loses to Jefferson in the election of 1800, the law expires. Adams’ Federalist Party never wins the presidency again.